Description

ALS

three pages on two adjoining sheets, 4.75 x 8

December 20, 1870

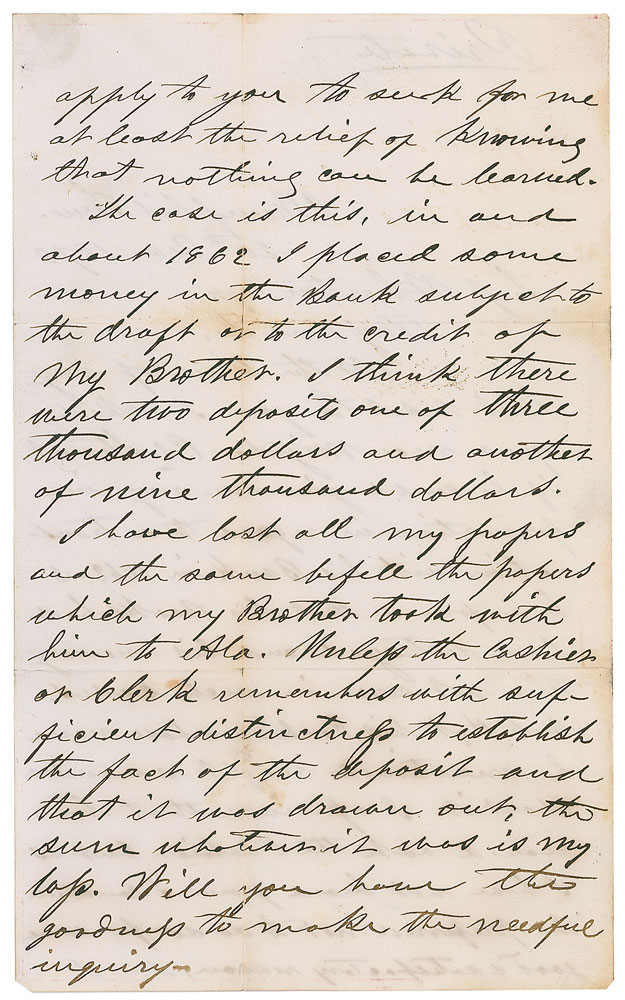

Letter to T. G. Wharton Esquire, marked at the top “Private.” In full: “At the time of my last visit to you I asked your near neighbor Col. Stewart if he could give me any information in regard to a transaction with his Bank in 1862-3 he informed that his books had been destroyed and his memory did not serve in such cases but that his cashier whose name he mentioned might remember about it. I assumed that he would ask the cashier but as I have not heard from I concluded he preferred not to do so for some good & satisfactory reason, so I apply to you to seek for me at least the relief of knowing that nothing can be learned.

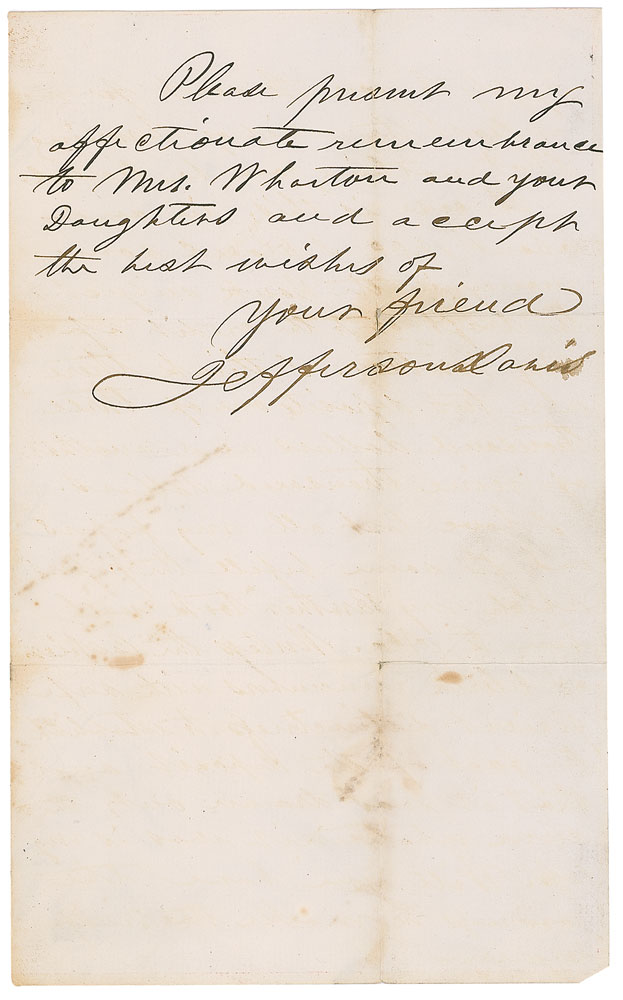

The case is this, in and about 1862 I placed some money in the Bank subject to the draft or to the credit of my Brother. I think there were two deposits one of three thousand dollars and another of nine thousand dollars. I have lost all my papers and the same befell the papers which my Brother took with him to Ala. Unless the Cashier or Clerk remembers with sufficient distinctiveness to establish the fact of the deposit and that it was drawn out; the sum of whatever it was is my loss. Will you have the goodness to make the needful inquiry. Please present my affectionate remembrance to Mrs. Wharton and your Daughters.” Intersecting folds, one through a single letter of signature, an ink blot to end of signature, two tape remnants to reverse of second page, and scattered toning and soiling, otherwise very good condition.

In February 1862, the newly reelected Confederacy president, concerned about recent military disasters in Tennessee and his reelection, worried about the family’s personal fortunes. On February 21, he penned his brother Joseph that their wealth was at stake should the Union penetrate into Mississippi, writing “Your property would be the next to my own an attraction to the plunderers It therefore seems to me that it might be well to send away as far as possible all which is mine, to send away, even up the Big Black, your cotton and valuables, and be ready to move your negroes and part of the stock.” To that end, Joseph funnelled the two deposits mentioned above “in the Bank.” By May 30, the Davises’ homes had been destroyed and he wrote his wife not to worry about “personal deprivations.” When Lee surrendered in 1865, Davis advised his wife to to take the “little silver” which was “scant store” and sell the land in Mississippi in order to find safe haven in a foreign country. He also returned property he had previously bought to the heirs of the former owner when he was unable to continue payments and declared that he staked all his property and reputation for the Confederacy, money which he personally spent for the cause plus the reminder that was “seized, appropriated, or destroyed.”

When he was released from his prison two years later, Davis found himself desperately in need of money, and expecting no compensation, he became president of the Carolina Insurance Company in Memphis, Tennessee which failed four years later. Trying to rebuild his life and gain control of his plantation Brierfield, he sought the help of Thomas G. Wharton, Esq., the Attorney General in Mississippi, to help reclaim lost money deposited by Joseph into a southern bank via the clerk, Col. Stewart. His personal papers lost, no hard proof of the deposits and his brother recently dead, it is not known whether Davis recovered this money, but he regained his estate, only to lose it. He lived on the charity of long-time admirer Sarah Ellis Dorsey who offered her cottage, Beauvoir, as a home and the rest of his life was spent writing his book The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.